Media outlets are experiencing a decline in sales and reach. Public confidence in the media is sliding and there is a lot of competition from social media and an overabundance of free offerings on the web. These are just a few of the challenges facing the media today. Is this the time to expect media companies to ensure hiring of diverse personnel and coverage of niche topics? Our answer: yes!

Diversity is not just about equal opportunity or social representation. More diversity brings in new target groups, new readers and viewers and, above all, better, more successful journalism. It's all about trust, credibility and so much more – things which have been missing in the German media for years.

I don't think that diverse editorial teams are just a question of fairness. I think they affect our ability to create world class journalism. They influence our access to stories; they affect our ability to represent the world in creative ways.

Joanna Webster, Thomson Reuters

New Target Groups

Some editorial departments seem to assume that their audience is basically the same as it was fifty years ago, strikingly homogeneous. Yet studies prove the opposite. More and more people are openly identifying as LGBTIQ*. Younger people are becoming more confident, open, and visible about their sexual and gender identities. So that potential target group becomes even larger when one considers that LGBTIQ* also have friends, acquaintances, and family members who are also interested in the topic.

The same is true for immigrants and their descendants. Even if some journalists or television editors are of a different opinion: people with an immigrant background also get their information mainly from German-language media and are entertained by German television. However, studies also show that people who do not look “typically German” often do not find themselves represented in the media and sometimes perceive reporting as stereotypical and discriminatory.

Likewise, people with disabilities use television at least as much as the general population. Unlike the rest of society, however, they regularly encounter barriers such as a lack of subtitles or audio transcriptions. And it goes without saying that women use media just as much as men. Nevertheless, they are clearly underrepresented. There are still two men for every woman on German television, and daily newspapers have unfortunately not yet focussed on female readers.

Viewed positively, this means that media companies now have the opportunity to recognize these new target groups and to start addressing them. How?

- By striving to incorporate underrepresented groups more: People with disabilities do not only exist in the context of health, social affairs, and mobility. Muslims opinions are not limited to the subject of headscarves, and black people do not only want to talk about racism. Women are interested in more than women's magazines or love stories, and LGBTIQ* people don't all read trendy magazines.

- By reflecting stereotypes in their content and coverage and reporting on issues that interest new audiences. [LINK]

- By ensuring there is more diversity in their newsrooms. [LINK]

- By offering content without barriers. [LINK]

- By showing a cross-section of society across all formats, from talk shows to daily soaps to Vox pops. The same applies to interviewed experts - regardless of the topic.

- By opening up established formats and creating new formats for journalists from underrepresented groups

- By choosing images that reflect the full diversity of people in the circulation area. This is especially true for topics of general interest such as health, pensions, education, or the weather.

![[Translate to English:] Mediennutzung von Menschen mit Behinderung [Translate to English:] 61% der Ertaubten sind unzufrieden mit der Barrierefreiheit im deutschen Fernsehen. 43% der Hörbeeinträchtigten sind unzufrieden mit der Barrierefreiheit im deutschen Fernsehen. 48% der Blinden sagen, dass sie den Inhalten im Fernsehen „gelegentlich” (24%) bis „oft” oder „sehr oft” (24%) nicht folgen können.](/fileadmin/user_upload/Infografiken/mediennutzungMmB.png)

One of the tasks of journalism is to reduce complexities - not always easy in a world with increasingly complex identities. That's why we need a journalistic concept of intersectionality. One that makes it clear that gender is not just a matter of legibility, but of visibility and tolerance. One that uses self-designations confidently and understands that our audiences are much more informed and diverse than we think.

Jess Türk, Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg

New Narratives

Male, white, university educated, non-disabled, cisgender and heterosexual: this describes most executives in German newsrooms to this day, and additionally, the view of the world they present in journalistic writing and reporting. Yet reality has so many more exciting topics, stories, and perspectives to offer. These stories can best be told by media professionals with an eye for them.

A wheelchair user can tell completely different stories about municipal traffic planning than the colleague who drives to work in an SUV. A journalist whose parents were dependent on welfare payments probably has a completely different approach to the unconditional basic income scheme than his or her colleague from a family of doctors. People whose gender identity is constantly questioned have a different view of femininity and masculinity than those for whom the entry of gender in their passport and name on their bank card never played a role.

Muslim queers, wheelchair-bound trans* men, Black East Germans offer an invaluable pool of new perspectives and topics. Here are stories for the media of a pluralistic society and these stories are not just "niche topics." And even if they were, how many viewers watch reports about the stock market on TV? And yet such reports still exist.

Important competencies

One of the long-known truths voiced in management literature is that heterogeneous teams deliver better results. This also applies to media companies. Diverse teams

- often have varied and new perspectives,

- question each other and thus reduce the risk of mistakes,

- are on average more profitable than homogeneously composed groups of employees.

Diversely staffed newsrooms benefit from new perspectives, experiences, and skills that are often lacking in journalism, such as:

- intercultural and subcultural knowledge

- the ability to mediate and translate for mainstream audiences

- the ability to question gender roles and other "norms" that otherwise are often not addressed

Furthermore, they

- offer access to communities and their issues

- access to different networks and experts, interview partners, protagonists

- multilingualism - incl. sign language

- expertise in new (specialist) fields

- personal experiences, e.g. with racism, sexism or other forms of discrimination

These are just some of the benefits of diverse editorial teams. How often do error-prone translation programs have to take over research in Turkish, Russian or Arabic because there is no first-language speaker in the editorial team? How often do non-disabled editors comment on political programs for accessibility and disability inclusion in urban development? How often does it go unnoticed when the coverage of LGBTIQ* topics is embarrassingly generalising, or talk show guests are once again predominantly all white and male? And does anyone in the newsroom notice that most journalists speak academically tinged German?

Let's face it: a lot of media content is hard to understand for people who haven't been to university. And most people in Germany haven't. So, if you want to understand and address migrant communities, queer subcultures, and "the man/woman on the street", you should stop excluding them from your editorial staff.

At the same time, media professionals need to note that a colleague who brings diversity to the newsroom mustn’t necessarily be limited to topics connected to diversity. A disabled journalist does not automatically have to be given the task of being a watchdog for everything related to disability. But if a lesbian editor signals that she wants to take on LGBTIQ* issues, go for it!

In any case, there should be more exchange in editorial offices about who reports what, when, and why. Is it more about looking at diversity in society in general or is it more about showing off the peculiarities of “bizarre” minorities? These questions should be discussed regularly and usually get resolved in diverse teams.

Der Berichterstattung über queere Themen fehlt die Expertise. Feste Fachredakteur*innen gibt es in aller Regel nicht. Während zu Themen wie Parteipolitik, Verkehr oder Literatur ganz selbstverständlich – und zu Recht – Fachjournalist*innen Vorrang haben, ist LGBT ein Thema ‚für alle‘, egal wie gut vorgebildet oder vernetzt sie sind. Expert*innen mit queerer Lebenserfahrung und Kontakt zur Szene wird im Gegenteil unterstellt, ‚zu betroffen‘ zu sein. Dadurch tritt die Berichterstattung auf der Stelle. Uralte Fragen werden als originelle Kontroversen verkauft. Überholte Begrifflichkeiten werden benutzt. Die Berichterstattung ist häufig eingeengt auf ‚erste Person dieser oder jener Identität in einem Amt, auf einem Magazin-Cover oder in einer Serie‘. Die Lebensrealität von Queers wird oft erst dann sichtbar, wenn sie Gewalt erfahren.

Peter Weissenburger, taz

How important is it to you for people with an immigrant background to be seen and heard in the German media?

![[Translate to English:] Identifikationsfiguren in den Medien Question posed to 20-to-40-year-olds with a migration background](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/a/csm_identifikationsfiguren_a56ac139e5.png)

More Credibility

Social psychologists have known for a long time that we are most likely to trust those who are similar to us. We recognize ourselves in people who are similar to us in many ways. Their stories tend to touch us because they could be our stories.

Studies on diversity in media companies also show that journalists with different cultural and biographical backgrounds bind a diverse audience and strengthen audience’s trust in the medium. They are role models and characters to identify with.

In addition, in the eyes of more and more media consumers, social representation is becoming the yardstick for evaluating journalistic offers. Editorial offices and programs that no longer reflect the reality of our society are losing credibility.

Most of what so-called non-disabled people know about people with disabilities, they usually learnt from the media. The images portrayed by the media are therefore crucial.

Schauspieler und Aktivist Peter Radtke

Image-Gewinn

Mediale Eintönigkeit wird zu einer Bedrohung fürs Image. Die Zeiten, in denen Männer im „Internationalen Frühschoppen“ unter sich das Recht auf Abtreibung ausdiskutieren konnten, sind zum Glück lange vorbei. Die Zeiten, in denen weiße ohne Beteiligung von Schwarzen Menschen und People of Color (BIPoC) über Rassismus diskutieren, sind es hoffentlich auch bald.

Medien, die diese gesellschaftlichen Entwicklungen ignorieren, bekommen es heute in sozialen Netzwerken und anderswo schnell mit einer zunehmend kritischen Öffentlichkeit zu tun. Wer nicht mit der Zeit geht, landet entweder im Shitstorm oder – schlimmer noch – in der Bedeutungslosigkeit.

Representation of LGBTIQ* in the media is increasing but has also become more challenging. As a non-binary lesbian, I want visibility of all sexual and gender identities in speech as well as in representation and pictures. Critics need to know that doing this does not take anything away from anyone. It is not a cake to be shared. Let's finally make what’s still considered special normal. Let’s get to participation and visibility everywhere.

Luca Renner, ZDF Television Board, ARTE Germany Advisory Board member, Queer Media Society

In Future

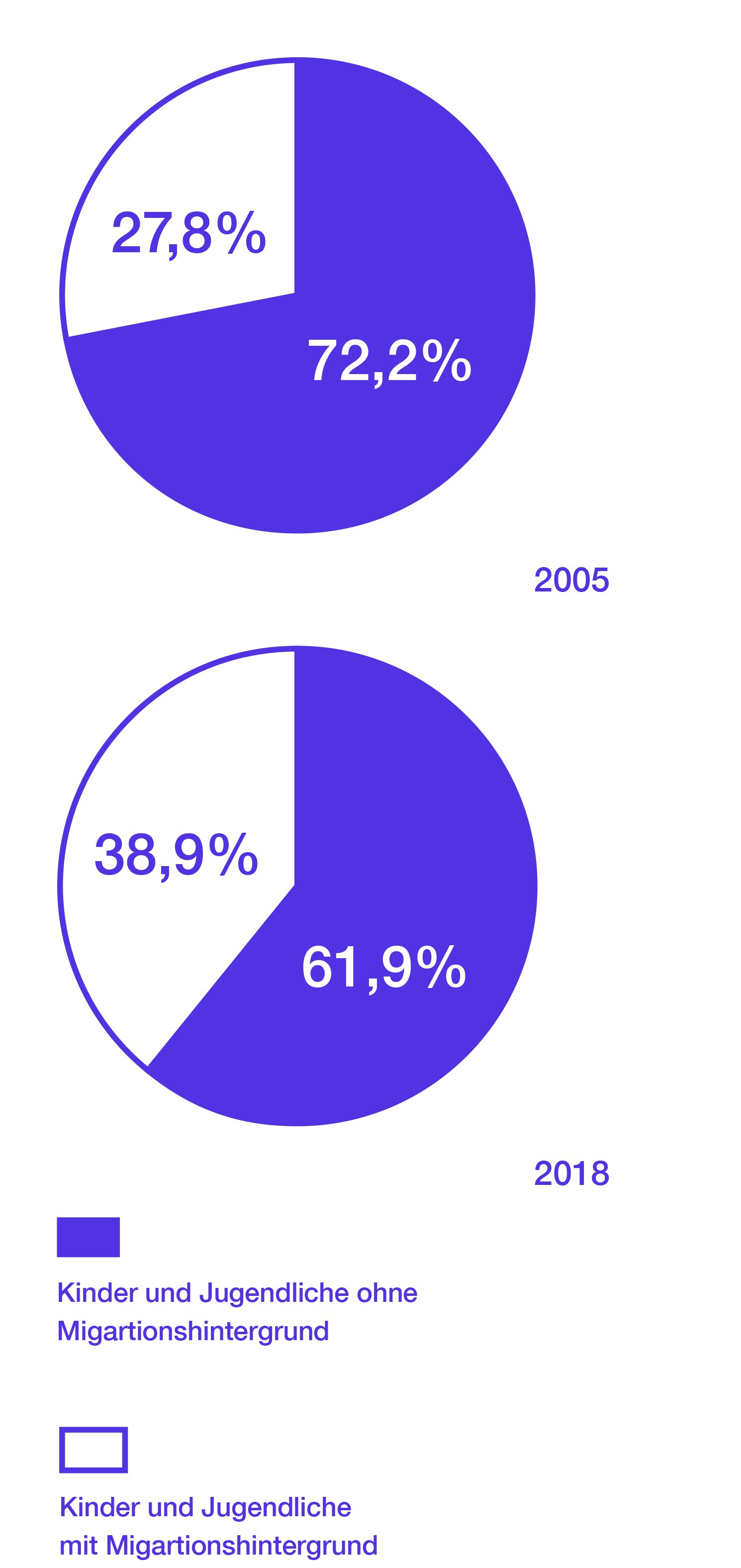

Social change cannot be ignored. The number of people with a migration background in Germany was 26 percent in 2019. (11) Among children under the age of six, 40 percent are already the descendants of immigrants (12) and in all major German cities the supposed minority is now the majority.

So now, the media is being confronted with a fundamental question: Are we taking steps to keep pace with our changing societies, or are we waiting until we have missed the connection with the real world? Media outlets that fail to act today are already saying goodbye to their own futures.

Fortunately, more and more German media outlets are realizing how important the topic is and they want to meet international standards. They are trying to open their editorial rooms to people from a wide variety of life experiences who can bring in formats for new target groups.

- What does BIPOC mean? (Black Indigenous and People of Colour)? Many Afro-Diasporic people in Germany today use the term "Black" as a self-designation. "Black" in this context is not about skin colour (who is black anyway?), but is used in contrast to “white” (people perceived as either “German” / “European” / “Christian”). The term Black also stands for anyone who doesn’t "pass" as white. To make it clear that it is a self-designation, word “Black” is usually capitalized. Other minorities that are subjected to racism also classify themselves as People of Colour. A tip for our white readers: don’t ever use the term “coloured”, as that would be reverting to colonial language.

Our Democracy

Society needs journalists. It is they who inform people and enable the formation of political opinion. The more homogeneous editorial teams are, the more difficult it is to bring diverse perspectives to the work and to address issues in society without prejudice. The more diverse editorial teams are, however, the easier this job becomes and the more successful it will be. Editorial teams made up solely of white men of a certain age miss out on many developments.

And just as it’s impossible to imagine an all-male newsroom or editorial team today, it ought to be impossible to imagine an all-white newsroom.

Especially when you consider the media's special constitutional mandate in terms of equity of access and the representation of all groups of society in the media. This holds especially true for publicly funded broadcasting houses.

Quelle: Julia Krüger Photography

Quelle: Julia Krüger Photography