Diversity is important to many department heads, but they don't want to have to put in too much effort to achieve it. That was the finding of a survey conducted by the Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen in 2020. Apparently, there’s this assumption that it will take care of itself. Unfortunately, this is not the only misconception. Let’s now take a look at the most common misconceptions we face when striving for more diversity in the media.

"Those with talent will succeed."

Unfortunately, they won’t. Of course, there are many examples of female journalists, journalists with an immigrant background or from other minority groups who have become very successful in their fields. These journalists are however still the exception to the rule.

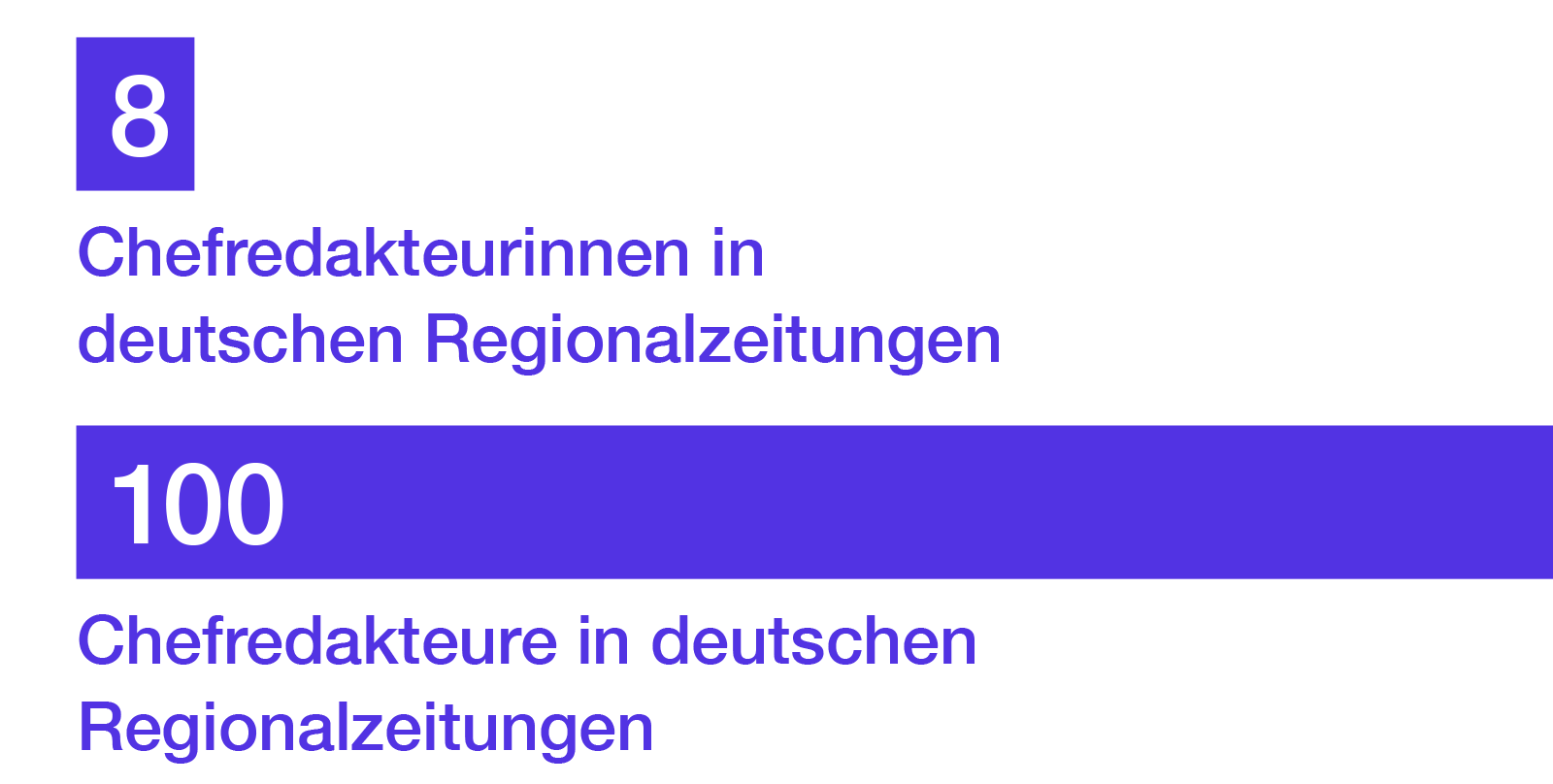

Research by ProQuote shows that although around two-thirds of trainees are female, they are still in the minority in management positions. Fewer than 10% of department heads at regional newspapers are women.

The situation is even bleaker for media professionals with an immigrant background. According to the last representative survey conducted in 2009, they made up less than three percent of editors.[1] Even if the numbers should have doubled or tripled since then, they would still be far below average. People with an immigrant background make up 27 percent of German society. And believe it or not there are still editorial offices without a single journalist of colour on the staff. The following misconceptions help to explain why this is still the case.

Basically, my observation is that women over 45 are no longer held in good esteem by bosses. For many years, I was no longer sent to training courses or allowed to participate in in-house projects. My opinion was simply no longer sought after. I was no longer interesting. Editor of a regional newspaper

“We’d like to hire, but we can’t find applicants.”

That's not because they don't exist. Each year we receive over 100 applications from aspiring journalists with an immigrant background for our mentoring program for young journalists (die NdM-Mentoringprogramme).[2] So, if media companies do not manage to attract them, there are good reasons:

- Image: A media company that does not show diversity either in its reporting or in its staff structure has little chance of being considered an attractive place to work. But if there are role models, for example, if the editor-in-chief happens to be openly lesbian, applications from corresponding candidates will come automatically.

- Calls for applications are rarely formulated and illustrated in a way to appeal to a diverse range of young people. Those who don’t feel addressed don’t apply.

- Visibility: Posting trainee positions or job openings on your company’s website and then waiting for diverse candidates to apply isn’t enough. If you really want to reach out to a diverse group of media workers, try additional channels, for example, networks such as Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen or Leidmedien.

- Requirements: Expecting a master's degree from young candidates but not recognizing any professional training they may have already done, or requiring them to do a number of unpaid internships further ensures that young journalists continue to come from financially secure middle-class homes.

- Assessment: Why should trainees be able to list the names of all the German chancellors since the war, but don’t need to know the names of the top politicians in the GDR or when the next Ramadan or Hanukkah celebration begins? If you are looking for diverse talents, you should also appreciate diverse knowledge.

- Prejudices I: Research has shown that applications are often unsuccessful if the name of the person applying does not sound typically German.[3] Knowing this, many good candidates therefore don’t bother to apply unless they are explicitly addressed. This applies especially to well-established media houses or institutions with a particularly elitist reputation.

- Prejudices II: People talk. When the German language skills of candidates of colour are directly or subtly questioned in a way that those of white candidates are not, the word gets around. Or when in a job interview joke are made about the communities of these candidates, about how religious, fanatical or otherwise different they are, a good conversation becomes almost impossible. And since word gets around, very few candidates want to expose themselves to such situations. They’ll try their luck elsewhere, in less elitist or established media institutions.

- Passivity: If you want to attract young talent you should try a direct approach. Try sponsoring student newspapers in schools with a large percentage of immigrant children, support workshops in youth centres which they frequent, provide scholarships for internships, or simply participate in the mentoring program of the Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen.

I never thought I'd end up working as a journalist. I've always had this dream in the back of my mind - journalism is one of the most exciting professions there is. But being able to become a journalist myself didn't seem realistic for a long time. Maybe it was because I lacked role models. Nil Idil Cakmak NDR editor, member of the board of Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen e. V.

„We offer equal opportunities for all. “

In all likelihood, that's not true. The entry into journalism is not decided only during the application process. Exclusion mechanisms often take effect a lot earlier. For example, you don’t have to go through a single standardized training course to become a journalist. Many paths can lead into journalism. In theory, access is open to everyone, and anyone can call themselves a journalist. This in turn guarantees freedom of the press and freedom of opinion. In practice, however, good contacts, networks and strong connections facilitate the path to journalism. Instead of fixed requirements, “who you know” also counts.

The buddy culture in journalism is white, cis-male, heterosexual, German, university educated and without disabilities. The consequences are felt by young women, for example, whose entry into the profession sometimes depends more on their looks than their performance, and who are promised advancement opportunities in exchange for sexual "favours." Abuse of power and (sexual) assault are not unique to big tabloids.

Getting a foot in the door is not easy for young journalists from immigrant families, poor backgrounds, or both. They lack the good connections and the educated bourgeois background. In the German media, which stable you come from is often just as important as talent and qualifications. Equal opportunities are practically non-existent.

In contrast, mentors can be of decisive importance for young journalists. They can compensate for a lack of contacts and be collegial allies. Equally, networks such as Leidmedien or the Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen are places of support.

"I will never be able to get rid of him/her again.”

This is one of the most common prejudices that prevent employers from hiring people with disabilities. However, disability laws that protect people with disabilities from being fired do not prevent firing for reasons non-related to the disability. In Germany, the Integrationsamt (Integration Office) examines all sides of a dismissal case and looks for solutions to help the disabled person to keep their job.

Gross individual misconduct is cause for dismissal – whether the employee has a disability or not. A lazy employee who celebrates illness or insults colleagues must expect to lose their job. This applies to all employees alike - with and without disabilities. Supervisors who apply the same standards to their employees with disabilities as they do to everyone else have nothing to fear.

“They all want to become doctors or lawyers."

This argument is often used by decision-makers to justify the lack of journalists with an immigrant background, as was shown, for example, in a study of media companies in North Rhine-Westphalia.[4] There is some truth to this. When young people from immigrant families decide on a profession, journalism is seldom the first choice. This is because most young people – regardless of whether they are the children of immigrants or not - often choose their profession based on role models in their families or among their acquaintances. Moreover, journalism is not a “safe” profession. That is to say, it comes with more risks than other professions, and not everyone can afford those risks. For instance, young journalists often have to start their career as freelancers without a regular income, never knowing beforehand whether a piece or feature will get sold. It takes a lot of self-confidence or the financial support of the family to go down this path. If that backing is lacking, journalism is not an option.

A colleague once took her parents on a tour of our editorial office, and at each desk she introduced the colleague she works with by name. This is Rita, this is Jens, this is Claudia.... At my desk she said: "and this is Ferda, our Turkish colleague". I'm sure she didn't mean anything by it, but I was the only one she reduced to one characteristic. And from then on, I wondered if the others saw me in the same way.

Journalist and author, Bundesbeauftragte für Antidiskriminierung

"Women don’t really want to climb the career ladder”.

Women are still being prevented from getting ahead in their careers. It is often assumed or implied that they would rather be housewives, staying at home and taking care of their families. The figures tell a different story. A representative survey of more than 5,000 employees and students came to the conclusion that 37 percent of women want to pursue a career. The figure for men was only slightly higher at 43 percent. When asked how confident they were that they would succeed in their careers, the differences were even greater: 47 percent of men, but only 39 percent of women were optimistic.

In short: women do want to pursue careers, but unfortunately, they are often not allowed to.

If you were to ask the editors-in-chief, they would say: all paths are open to women. (...) But I was rejected for all the positions I applied for. Always with reference to my request for wanting to work part-time (80 percent position). Editor of a regional newspaper

"They are biased on so many issues. “

In some editorial departments, certain life experiences or diversity characteristics seem to be considered a disadvantage. Looking through the eyes of a "migrant" or "queer person" apparently distorts neutrality. While the attributes "white," "Christian," "male," or "heterosexual" supposedly have no influence on a person’s worldview, BiPoC, headscarf wearers, or people with disabilities are often considered activists “by nature”.[5]

Confusing neutrality with normality has absurd consequences: Major broadcasters have long avoided employing native speakers as chief correspondents in their foreign studios. Instead of taking advantage of the fact that native speakers can get closer to people and stories, they distrust their professionalism.

It's a good thing that more and more stations are moving away from this practice. If one really believed this prejudice, one would also have to exclude all “German” journalists from the Federal Press Conference and replace them with immigrant journalists, because the latter are less biased. At this point, you will realise how ridiculous such arguments are.

"In Germany, German views apply."

What exactly is this "German" view, one may ask? Is it Horst Seehofer's or Claudia Roth's? Is it that of the BILD or that of the taz? The so-called German view is similar to the view on journalistic neutrality. It is an illusion that is always brought on as an argument when people start defending privileges. Because, of course, there is no ONE German point of view.

Two Germans can hold very different and very contrary perspectives. That’s what we call freedom of opinion. So why not welcome and appreciate the perspectives of immigrants and New Germans as additional facets of diversity?

Holding high the “German view" is a form of internalized prejudice. It’s saying that immigrants, Blacks, or refugees can’t be German or hold “German views”. So whose viewpoint is it when Rom:nja are only mentioned in connection with criminality and poverty? And when the same crime (husband kills wife) is called "family drama" in the case of a white German couple, but "honour killing" in the case of a Muslim family, whose point of view is being represented?

"They can’t climb our stairs”.

Applicants* with disabilities are familiar with this excuse. Similar concerns are: "Are our doors wide enough for a wheelchair?" or "How is journalism even supposed to be possible with a disability?" But not all people with disabilities use wheelchairs or need elevators. Disabilities are as diverse as workplaces are, and people with other disabilities experience very different barriers - for example, blind employees need assistance with communication software or special devices. And by the way, a few stairs can often be maneuvered with a ramp.

There are many solutions to create an accessible workplace for people with disabilities, once the will is there.

I heard phrases like, 'We're doing more book reviews and cultural programmes now, but you can't do that because you're blind.' I was also asked in the job interview ‘Are you sure you can really manage the task, after all, you're blind?' And during my traineeship, it took seven months for me to be provided with a screen reader. Someone even had to help me write my term paper until I got it. I also wasn't allowed to attend any television seminars. After the traineeship, I could barely make ends meet with the payments I got for my work, so I sought advice at the employment agency. They told me: 'Why don't you go to the school for the blind in Düren and train as an office administrator, and maybe then we'll be able to find a job for you?’’

Journalistin Amy Zayed

"A good journalist can report on any subject."

Theoretically, that’s true. Good journalists know how to research topics and can then report on anything. What does this look like in practice? Let's look back to just a few decades ago. As has already been mentioned, editorial offices were almost exclusively staffed by men, with the exception of a few female journalists who were allowed to take on the so-called "women's topics” such as fashion, recipes, and subjects related to family affairs. Male editors simply ignored women's issues, and women journalists were usually paid less than their male colleagues because their topics were considered less important. Few women at the time seemed bothered by this. Fortunately, that has changed; women can now be found at all levels in journalism. As a result, certain issues that are of particular concern to working women are now taken more seriously - for example, flexible working hours, children’s day care services and even reproductive medicine.

In other words, the perspectives of editorial teams with balanced gender diversity complement each other. This holds true for all sorts of other characteristics as well. An older female journalist will bring in a different perspective to a story than a younger colleague, just as a female academic will probably see different aspects of a story than a non-academic. In the same way, a journalist with an immigrant background probably views his environment in a very different manner than the female colleague without one.

Balanced reporting thus also depends on the composition of the editorial team. The more diverse a team is, the more nuanced the reporting becomes. I the end, it’s a win-win situation for all, because more nuanced reporting in turn also attracts a more diverse audience. Everyone benefits.

I handed in my application for a job at the Nuremberg Newspaper (NZ), on the date of the deadline. I didn't tell anyone about it because I thought everyone would think I was a crazy. I had only been in Germany for twelve years at the time and, apart from my NZ internship and a volunteer job in the Russian editorial department of a left-wing radio station, I didn’t have any major qualifications. And the NZ took me on! What madness, right? They told me 'All the applicants we shortlisted could write well. But your biography was so different. We think you can bring other perspectives to the reporting. That would be good for our institution.

Ella Schindler, Editor, Nürnberger Zeitung, Member of the Board of Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen e. V.

“Our audience doesn't feel represented by immigrants."

If this is really true, you need to ask yourself what conclusions this leads to not only about your audience but also about your own content. In the case of most media products, however, the numbers speak a different language.

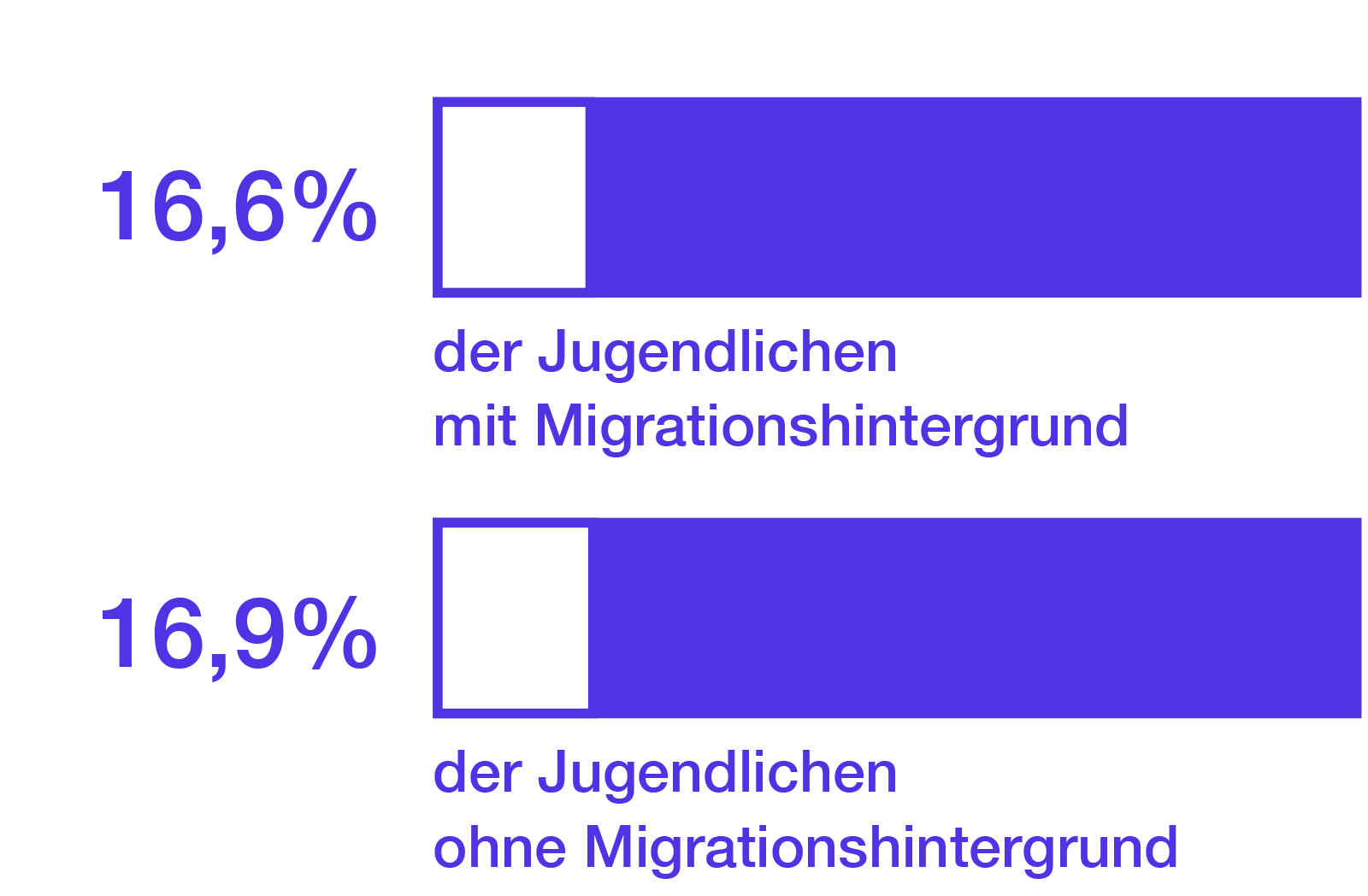

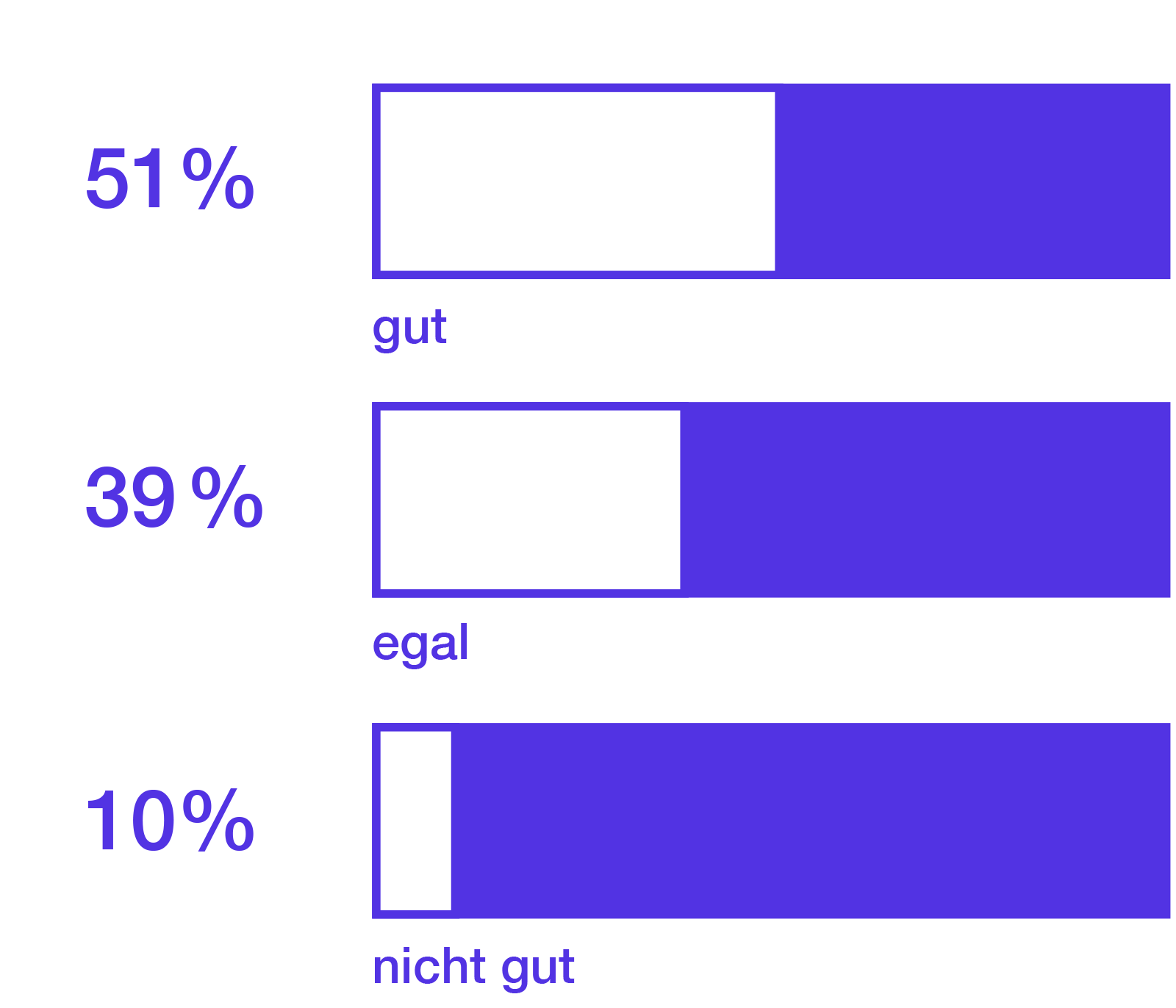

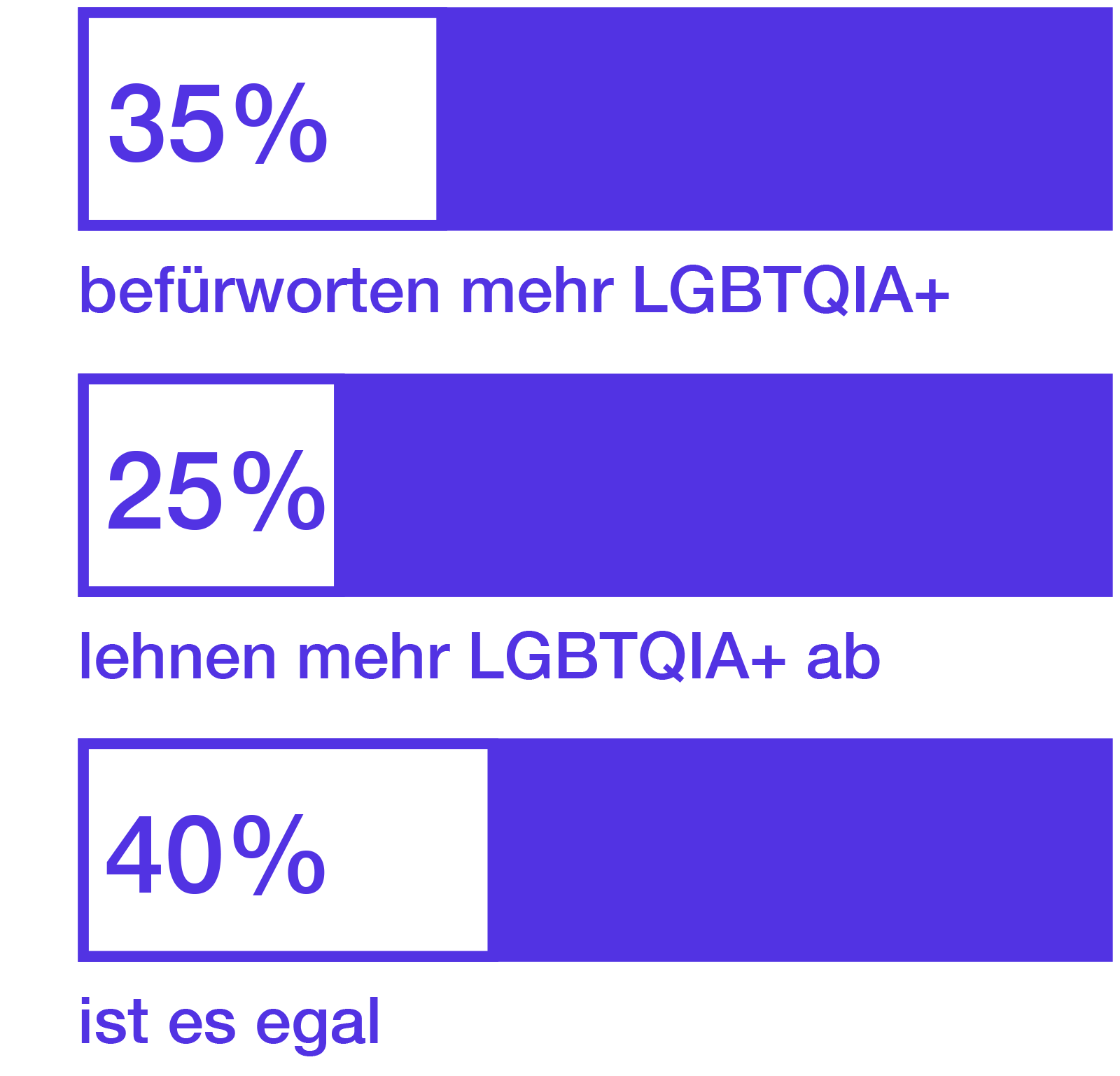

Instead of using outdated concepts about what „our readership / listeners / viewers” want as the basis for decisions, it's better to ask the target groups themselves. In representative surveys, media consumers have expressed wanting a more diverse cast of characters. A large proportion don't care either way, and younger viewers in particular are not only open to ethnically diverse voices and faces, but they also actually demand them.

"If more actors and presenters of diverse ethnicities appeared on television, how would you find this?". Source: RTL, representative Forsa survey, "Opinions on more integration in the media," 2011

“I can't expect our viewers to listen to presenters with accents."

Why not? In the English-speaking world, different accents are normal, but not in Germany. You’ll hardly hear any kind of accent on German radio. "I hardly know of anyone in public broadcasting with one," says radio journalist Vera Block, adding, "But when it comes to eyewitness reports from the countries of origin or from diasporic people here, an accent seems to be less of a problem."

In the U.S. we see a very different picture. You hear different accents on the radio all the time both among presenters and among their guests. Diversity policies encourage this since they are aimed at increasing representation and media is expected to portray a cross-section of society.

In the radio and TV business, having such policies in place are even a pre-requisite for a broadcasting license. Ensuring ethnic diversity is even a requirement in privately financed broadcasting institutions. None of them have lost viewers or suffered diminished coverage because of this. Ethnic diversity is simply part of the broadcasting business in the US.

It's just as rare to see and hear media professionals with speech impediments in this country. But if a popular and esteemed literary critic like Marcel Reich-Ranicki could discuss books for decades despite his lisping, why shouldn't that be possible for a correspondent?

„They only want to write about topics such as feminism, racism or homo marriages.”

When I propose a story about Afro-Germans, I get to hear: "But you also have to offer topics that have nothing to do with you," says Anne Chebu, journalist and author of the book "Anleitung zum Schwarz sein" (Instructions for being Black). As if a personal connection with the subject matter would automatically make the report worse. If a music critic listens to Helene Fischer in private or the editor of the motor pages drives an SUV they are not automatically suspected of non-neutrality. All journalists often report on topics they are familiar with, have personal experience with, or are interested in.But intercultural and subcultural competencies can also become a stigma. It’s not the lesbian, Russian-German or Jewish journalists who are not neutral, it’s the decision-makers, rather, who are not. It’s the heads of the editorial departments themselves who tend to put journalists in certain boxes: Muslims get to do the integration topics; gay people write about LGBTQ+ rights and Blacks get to cover racism. Only white, heterosexual German journalists seem to be able to write about any and every topic.

That’s not to say that journalists with immigrant backgrounds don’t want to report on topics such as migration, refugees, integration or discrimination. Often, they even have the advantage of being able to fall back on personal experiences. But just like other specialized journalists they too need to be allowed to cover a wider range of topics. People from immigrant families are not per se experts on migration, integration, Islam, anti-Semitism, racism or their parents' countries of origin.

When Ahmadinejad was still president of Iran, I was always asked, "What's going on there...?!" I remember when I interviewed for admission to the school of journalism, I was asked whether I saw him as "the mad man of Tehran," as a magazine had previously headlined. I had the impression that I had to justify myself for an embarrassing president. That made me very uncomfortable. Later, in a similar situation, I very quickly made it clear that as a German-Iranian, I may represent part of Iranian culture, but I am not an expert on politics.

Dena Kelishadi, Freelance journalist and reporter

"I cannot impose the additional burden on the editorial staff.”

Admittedly, journalists can also be prejudiced and be unsure of how to interact with people with disabilities, but these fears can be reduced and must never be a justification for discriminating against people with disabilities.

Changes will often be necessary when people with disabilities are hired. But ultimately, all employees benefit when the company becomes more inclusive: This includes opportunities to work from home, quiet rooms, and more transparent communication.

In my first job, there were communication problems in the beginning. In contrast to conversational situations with other people, I could hardly read my old editorial manager's lips and we had to communicate in writing. Only later did I realize that it had been a mistake not to have made sure that staff members with normal hearing receive training in communicating with hearing impaired colleagues

Thomas Mitterhuber, Editor.in-chief of the Deutsche Gehörlosenzeitung

“Thanks, but we already have a colleague with an immigrant background, with a disability etc. “

"We've already got a Turkish reporter" or "We've already got someone with a similar name" – these were some of the things journalists from immigrant families used to hear in the 2000’s when they or their work got rejected. We've never heard any editor-in-chief say, "Oh, that's too bad, we can’t hire you because we’ve already got a man at the news desk!" or "We already have a female editor, why don't you try somewhere else?"

Having said that, how effective can one single woman working in an all-male political newsroom be? Will she be able to bring in her perspectives and her own approach or is she more likely to adapt, behave, talk and write just like her male colleagues? There’s enough research on this. You need a "critical mass",[6] to create change. And that critical mass is thirty percent. That's why having just one or two minority representatives in an editorial department or newsroom are not enough to bring about change.

"Why should diverse media teams be better?“

Journalists who have experienced discrimination are neither better, nor more objective, competent, or more professional. But they are not worse either. The advantage in hiring them, however, is that they can bring different perspectives, new experiences, intercultural skills, and a fresh way of looking at things to an editorial department.

This may come as a surprise to some, but not all gay, Jewish or intergender journalists are the same. Like all other journalists, they have different areas of expertise and come from different backgrounds. Their advantage over their “pure” German colleagues however is their direct access to their respective communities. This kind of access to groups and communities is a way to uncover new stories, bring in new content and present new perspectives.

In addition, journalists who experience discrimination in their everyday lives themselves are usually better able to recognize discrimination or marginalisation when it affects others. They’re not always, but usually more sensitive to discriminatory language in their reporting and writing. That's the difference.

"My editors can acquire the necessary knowledge themselves.“

That's right, everyone can acquire additional knowledge. So, make sure your team does and support them in doing so! The best interview techniques are of little use if a journalist has never learned how to change perspectives or doesn’t know how transfer strategies work. Diversity skills can be learned and should be part of a journalist’s toolkit.

Having experienced personal discrimination may sharpen a person’s eye for certain perspectives, but it is not a guarantee for better journalism and certainly not a prerequisite. Professional reporting in a diverse society requires both well-trained and diverse media personnel.

Intercultural and subcultural competencies are qualifications like others, except that they are seldom recognized as such and unfortunately there are few professionals in journalism who possess them.

Quelle: Moritz Liss

Quelle: Moritz Liss